For over a hundred years now, the medical community has noted the disproportional impact that race and ethnicity has on the acquisition and spread of disease.

This has most recently been noted with the spread of COVID. The New England Journal of Medicine, Daniel B. Chastain, Pharm. D., August, 27,2020. Infectious diseases have shown these trends before, such as with Yellow Fever outbreaks and the 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic. It is thought that there are many contributing factors to this phenomenon. It is not only recognized in the black community, but also with the Latinx community and Native Americans. The question is whether there are certain predispositions for disease or there are other factors, such as economic, which play into this phenomenon.

I recently spoke with Tatsiana Keiko, MD, a pulmonary specialist at the Medical University of South Carolina Medical Center in downtown Charleston, South Carolina. She informed me that these trends are not just notable in current medical practice, but have been in past decades as well. Her contention has been supported by statistics gathered by the Center for Disease Control (“CDC”) and other medical institutions throughout the country.

Dr. Keiko noted that there are three conditions which have a higher incidence in the black community which contribute to more severe cases of COVID, they are: high blood pressure, diabetes and obesity. Healthy foods might not be as readily available for some. Since fresh fruit and vegetables, as well as better cuts of meat and fish are more expensive, they may be unobtainable for those with limited income. These same economic factors can have other consequences such as poor overall health and well-being. Lower incomes can impede access to medical care by inadequate or non-existent medical insurance, lack of transportation or availability of services. Poverty also creates difficult housing issues. Patients may have to share housing with other relatives or kin. Crampet housing shared with multiple family members can encourage the spread of germs or impede patients in their ability to self-isolate or maintain social distancing.

Distrust of the medical community and government connected programs is one of the greatest factors for some racial and ethnic groups. The syphilis treatment of the Tuskegee airmen and other black soldiers during WWII and the decades thereafter is a sticking point many cannot get past. These men of the armed forces were deceived for decades while they thought they were receiving treatment for syphilis, they were in fact given placebos such as aspirin and vitamins, while their symptoms were being recorded for study of the long-term effects of the disease.

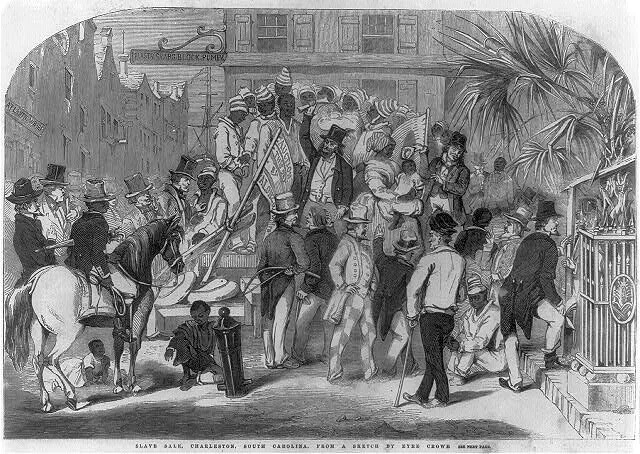

Similar studies with the tolerance of pain among women of color was also conducted. While enduring the substantial discomfort of childbirth, pain medications were withheld for black women while some medical authorities contended that they do not feel pain like white women do. (Reuters Health, November 12, 2019.) This school of thought was first introduced by Dr. James Marin Sims who started practicing medicine just a few brief months of medical study under another physician. Although born in South Carolina in 1813, he later moved to Montgomery, Alabama to start anew after his first few patients died. It was in this city that Sims building his reputation for treating enslaved women of color who were owned by rich white plantation owners.

Although considered an unsavory area of medicine, he started to study diseases of the female reproductive system so that slave owners could continue to ensure that their female slaves could continue breeding. His experimentation led him to develop a tool to greatly enlarge the vaginal vault for viewing and treatment or other intervention. He created a tool which enabled him to do this, the bent handle of a pewter spoon. It was the precursor to the modern speculum.

Black women are three to four times more likely to die from pregnancy-related causes than white women, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. It's partly why the overall rate of pregnancy-related deaths has climbed over the past two decades, making the maternal mortality rate in the United States the worst in any industrialized country, according to a 2016 analysis published in the journal The Lancet. The reasons behind the racial disparities are many and complex said Dr. Ana Langer, director of the Women and Health Initiative at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health in Boston. Lack of access and poor quality of care are leadings factors, particularly among women at lower socioeconomic levels. But there's a bigger problem, Dr. Langer noted. "Basically, black women are undervalued. They are often not monitored as carefully as white women are. When they do present with symptoms, they are often dismissed."

Statistics delineating racial disparities much like what we have seen in other health issues affected by ethnicity and race has been noted in the past year with COVID in various states and the nation as a whole. Earlier this year both Wisconsin and Michigan released data showing stark contrasts in the outcomes for people of color. Black residents in those states were twice as likely to be affected than the rest of the population. The New England Journal of Medicine, May 6, 2020.

Members of Congress such as Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) and Ayanna Pressley (D-MA) have called for more thorough collection and analysis of data on the matter. The experience of past epidemics and national disasters suggest that socially marginalized populations will suffer disproportionally. However, geographic disaggregation of COVID-19 data is welcomed but requires caution. Some already garnered data drilled down to the city level found that certain metropolitan areas such as Milwaukee, Chicago, New Orleans and Detroit have statistically higher numbers of cases. Sociologist Loïc Wacquant reports that such data presented by itself can cause what she has dubbed as “territorial stigmatization” where certain resource-deprived neighborhoods suffer from “blemish of place”. It may be an area with a garbage dump, tainted ground water or other toxic substance. In this scenario certain neighborhoods composed of poor people, minorities and foreign-born citizens which have already been marginalized by society perpetuate an image of undesirability. Roberts, Samuel Kelton, Infectious Fear: Politics, Disease, and the Health Effects of Segregation, Chapel Hill, NC, University of North Carolina Press, 2009.

However, in carefully collecting data and looking to factors beyond just socioeconomic status, but to other concerns such as economic inequality, it is clear that it is not just a problem of minorities. Of particular note is the role of stress or what is sometimes termed “weathering” or advanced aging caused by responses to external stressors. Weathering has been linked to cardiovascular disease and diabetes, two conditions which have been associated with an elevated risk for severe COVID-19. Braun, Lundy, Breathing Race into the Machine: The Surprising Career of the Spirometer from Plantation to Genetics, Minneapolis, MN, University of Minnesota Press, 2014. Moreover, there are place-based risks and resource deficits which impact such neighborhoods where preventative care is lacking, yet respiratory hazards and toxic sites might be located. So, while the neighborhood is minority-heavy, race and ethnicity are not the causal factors. In addition, it may be other matters such as unemployment, food insecurity and unstable or substandard housing may be conditions which perpetuate disparities. Continued research is indicated as the medical community works hard to diminish barriers to treatment and develop a more trusting and congenial environment.