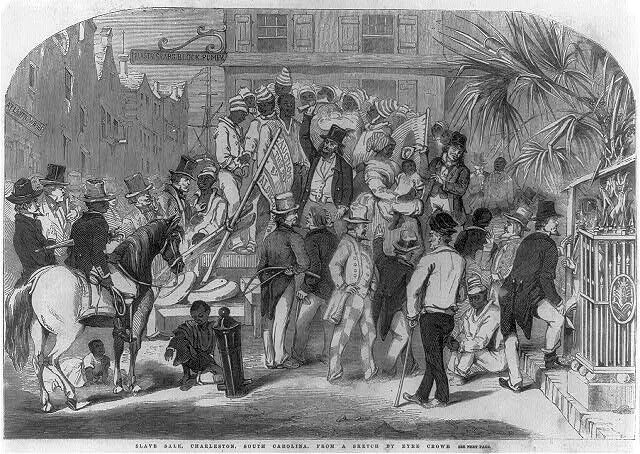

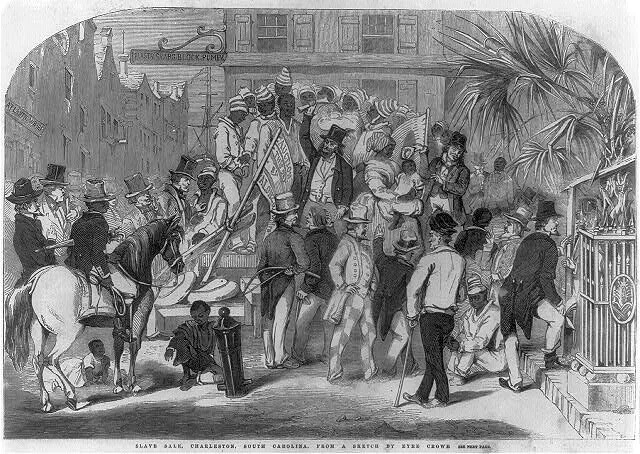

Charleston was the epicenter of the African slave trade. Over half of all newly enslaved people landed at Gadsden’s Wharf in downtown Charleston after traveling the Middle Passage from Africa and were sold into chattel slavery in the open-air markets, often in front of the Customs House near the waterfront. The International African American Museum (IAAM) will open later this year to educate people from all over the world as to this city’s sordid past of enslaving others.

Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress

Today nearly 84% of all people of color can trace their roots to Charleston, South Carolina. The white aristocratic planters accumulated great wealth because of the free labor provided by those enslaved. The enslaved field hands often worked as much as 18 hours a day commencing before sunrise or “day clean” until after dusk or “first dark”. They were given minimal food rations, including about 1-1/2 lbs. of meat a week and certain staple items such as flour and corn meal. Children were often not given shoes or clothing until they were five-years-old and able to “earn” such items. Adults were typically given one pair of shoes a year along with an allotment of fabric with which to make their garments.

The type of cloth they could use and the nature of the clothing items was carefully controlled by the Black Code, laws which were enacted to ensure the long-established informal caste system. This code was taken from Barbados’ black code established as far back as the 1600’s since Charleston was founded by people of British decedent who came here via Barbados. The system of forced labor by new African laborers as developed in Barbados involved frequent floggings, brandings and mutilations. The average life expectancy of a slave was seven years due to their harsh treatment. As their laws were adopted in Charleston, people of color were not permitted to wear fine clothes unless they were discarded items of their masters’. Moreover, blacks were forbidden to use a walking stick, fan, smoke a pipe or cigar as these were items traditionally carried by elite white planters as a sign of wealth. Blacks could not gather in groups of more than three. They were mandated to give way to white people when walking on city sidewalks, then lower their eyes as a sign of submission. To do otherwise could result in a whipping or even worse.

People of color were controlled by layers of authority figures in and around Charleston starting with their masters, drivers, overseers, the City Guard, the Slave Patrol and the city’s police. Because people of color outnumbered whites by a substantial number, as much as 4 to 1 or more, laws were developed early in the city’s history and such regulations were rigidly enforced. A disrespectful or recalcitrant slave could be taken to the Work House, also known as the “Sugar House” due its former status as a sugar refinery, to be tortured, whipped or even killed. The building had a dungeon and tortuous devices regularly used in the medieval era, such as stretching racks, iron masks and thumb screws. Along with this, there were multiple whipping posts wherein a cat-o-nine whip was used on prisoners which would slice the flesh with razor-like sharpness. Alternatively, an inmate might be forced to climb a hard to use treadmill designed to grind corn. They would have to work the treadmill for eight continuous hours a day. If they fell behind, they would be whipped. It was common for those engaged in its use to pass out from exhaustion or stumble and lose a limb in the process.

Travel was carefully controlled for people of color. To leave the plantation, a black person had to have a “ticket” or note from their master indicating their name, the place of origin and their destination. Free people of color (“FPC”) and those slaves who were rented out for a year or lesser period were mandated to wear “negro badges” or what was later known as slave badges that were fabricated by licensed silversmiths and watchmakers of brass, of tin or copper and distributed by the City Clerk of Charleston for a fee. Slave ownership and renting out those forsaken enslaved workers was a lucrative capital investment, considered much more profitable than stocks or bonds. Hence, a reliable system of controlling their movement was an instrumental behavioral restriction and a means to avoid a slave insurrection. The badges were stamped with certain information such as the year, the assigned number and the nature of the trade or position of the slave such as porter, mechanic or stevedore. The slave badges were punched to allow a string to be passed through it and had to be clearly displayed on one’s chest. Additional controls were in place to manage their travel hours. Black folks had to clear the streets by 9:00 p.m. in the winter and 10:00 p.m. in the summer. A drum would be beat ten minutes before the designated hour to alert them to quickly head home. They were also ban from walking near the White Point Gardens, a luxurious park near the tip of the Battery so as not to sully the view for aristocratic white planters. It is believed that these laws were the impetus for later “sundown laws” which controlled the movement of people of color in the more modern era and are still enforced in some regions.